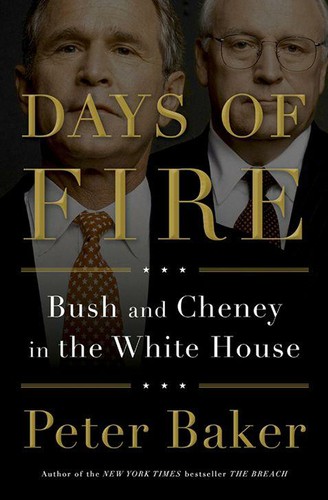

Days of Fire

by Peter Baker

My rating: ★★★★☆

Read From: 28 August 2014 - 18 September 2014

Goal: Non-Fiction

Peter Baker wrote a surprisingly even handed account of the Bush presidency. I say "surprisingly" because I was familiar with the antagonism between the New York Times and the Bush White House. I wasn't sure what to expect from a book written by a Times reporter. What I got was a well researched, balanced look at how Bush ran the White House and how decisions were made.

Baker starts the book with a back-and-forth look at Bush's and Cheney's early careers. He covers their respective college years, then moves on to their political years. He covers Cheney's years in Congress and in the Ford White House. He covers Bush's political efforts on behalf of his father, his time with the Rangers baseball team, and his time in the Texas governor's office. He focuses the majority of the book, of course, on their partnership while running for office and while in office.

The book wasn't just about the politics of the White House. Baker relates some of the interactions between Bush and his staff. Bush, like most Presidents, had many ways to torment his staff. Visits to the ranch at Crawford provided unique opportunities.

[H]e loved clearing brush, of which there seemed to be endless supplies.

Aides would be recruited to join the brush clearing and judged on their prowess and endurance in the sweltering heat. Stephen Hadley, the new national security adviser, was teased for showing up in tasseled loafers. (In fact, they were leather shoes with laces, but the loafers legend stuck.) “There was like a hierarchy that was completely different from any other hierarchy,” said Steve Atkiss, the president’s trip director who traveled regularly with him. “When you start, your job is basically, after someone cuts down a tree, to drag it out of there and put it wherever it is going to go. Then, if you really did good at that, the next level up was you could be in charge of making a pile of all the things that had been dragged over so that it burned well when you lit it on fire. If you were really good at that, you might be able to, one day, get to use a chain saw.”

I wasn't really surprised to learn that Bush liked to be thought of as a slow-witted dunce. He felt that it was an advantage to have his opponents continually underestimating him. I was surprised to learn that Cheney had a reputation as a moderate early in his career. People took his quiet, low-key personality to mean that he was far less conservative than he actually was. This benefitted him, as he started out.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the book was that Bush really was the Decider in the White House. Everyone interviewed for the book, and Baker interviewed many people, agreed that Bush was definitely in charge. Cheney had opinions and Bush knew what they were. But Cheney rarely spoke up in meetings and didn't dominate the conversations around the White House. Instead, it was very clear that Bush was in charge of each meeting and ultimately made each decision.

Early in his presidency, Bush agreed with Cheney on a great many things. The most obvious area was how to respond to 9/11 and what to do about Iraq. But they were also in agreement on domestic policy, such as tax cuts. Bush allowed Cheney to be the point person, in areas where they agreed. Cheney would work quietly, through his massive network of government contacts and loyalists. He was very effective at getting done what Bush wanted done.

Bush definitely made his share of mistakes and had character flaws. One of them, in my opinion, is that he deferred too much to trusted subordinates. Everyone needs to delegate, but I think Bush took it to an unhealthy level. One example is the de-Baathification of Iraq.

Saddam Hussein was the head of Iraq's Baath party. Some of the Baath party members were true believers, dedicated to Hussein and his methods. Most party members were not. They were only members of the party out of necessity, to hold a job and survive in a brutal environment.

Before the invasion of Iraq, Bush and his advisors debated what to do about the Baath party. Some favored disbanding it entirely and firing all of its members. Others favored a selective purge, of just the true believers. Eventually, Bush decided on a selective purge, reasoning that it would be too risky to dump many well trained and well armed people on to the streets.

After the invasion, Bush appointed Paul Bremer as his personal representative in Iraq. After getting to Iraq, Bremer decided to go ahead with a full purge of the Baath party. He fired everyone and put them all on the streets. Many of these people ended up forming the core of the Iraqi insurgency. Many experts believe that the de-Baathification of Iraq led to the insurgency and made it as bad as it was.

Bush had made the decision to only partially purge the Baath party. Bremer knew of this decision and decided to go ahead with a full purge anyway. Instead of overruling his deputy, Bush let his decision stand.

Bush was loyal enough to subordinates to trust their judgment ahead of his, once he'd delegated an area of responsibility to them. The de-Baathification of Iraq was just one example. There were others, throughout the book. I think this represented a real flaw in his leadership, as he failed to fully take ownership of decisions and enforce his own decisions.

While it often appeared that the Bush White House was lawless, doing whatever it wanted to in the name of national security, that wasn't quite true. Baker tells of one renewal of the NSA's wiretapping program, when the Justice Department objected to the terms of the renewal.

John Yoo was now gone, and a new crop of lawyers had arrived at the Justice Department, only to be shocked at what they found. Jack Goldsmith, a conservative law professor who had taken over as head of the department’s Office of Legal Counsel, thought some of the opinions he had inherited were poorly reasoned and unsustainable.

As a result, he refused to agree to the reauthorization of the program. A majority of the Justice Department's top leadership agreed with him and backed him up. Ultimately, the FBI did too.

The President was determined to renew the program, whether or not the Justice Department agreed. When he tried, however, a dozen administration officials threatened to resign, including Goldsmith himself and FBI director Mueller. Bush was forced to rescind his reauthorization and modify the program to comply with Justice Department and FBI requirements.

These kinds of conflicts—between Cheney and those representing the rule of law—continued to escalated. Increasingly, Bush began to side with everyone else. Baker demonstrates that Cheney and Rice represented the two sides to President Bush. Cheney represented Bush's impulse to protect America at any cost, going it alone if necessary. Rice represented Bush's impulse to work within the law, to build Congressional support for his policies, to work with other foreign leaders, to cooperate, and to build a reputation as an international leader rather than an international cowboy.

During the first term, Bush agreed with Cheney more often than Rice. But as the first term drew to a close, Rice started winning more of the policy arguments. When Rice moved to the State Department, at the beginning of Bush's second term, it was a clear signal that Bush was siding more with Rice and wanted her to have the clout necessary to carry out his desires. As the second term continued, Rice won almost all of the policy battles and Bush and Cheney grew increasingly estranged.

Ultimately, it become clear to me that Bush was who he claimed to be during the 2000 Presidential campaign. He was a moderate conservative, interested in domestic achievements that reached across the aisle and in building consensus among foreign governments. The 9/11 attacks shocked him, threw him off balance, and pushed him to respond in drastic ways.

Bush began correcting course at the end of the first term and became increasingly moderate throughout his second term. Ultimately, the dictatorial White House that the press loved to demonize didn't truly exist. The aspects of it that did exist were a reflection of Cheney's policies and Bush's agreement with those policies in the months after 9/11.

As Cheney and Bush grew apart, that image of the White House became less and less accurate. Bush was his own man, fully in charge, and capable of growing in office. But he was consistently identified with his Vice President and the public's image of him reflected the Vice President's policies and not his own policies. I think history will remember him far more kindly than people do today.

This is how Baker sums that up, at the end of the book.

And yet to blame or credit Cheney for the president’s decisions is to underestimate Bush. “Bush had a little bit of Eisenhower in him,” said Wayne Berman, “in that he didn’t mind if people thought that he was the sort of guy who was easily manipulated because it also meant that his opponents underestimated him and the people around him thought they were having more influence than they really were. And he used that always to his advantage.” While Cheney clearly influenced him in the early years, none of scores of aides, friends, and relatives interviewed after the White House years recalled Bush ever asserting that the vice president talked him into doing something he otherwise would not have done.

Bush, in the end, was the Decider. His successes and his failures through all the days of fire were his own. “He’s his own man,” said Joe O’Neill, his lifelong friend. “He’s got the mistakes to prove it, as we always say. He was his own man.”